NASA hangies in space? pt.3

NASA and a kind of paraglider:

During these 1960s experiments all parachute-related devices were referred to as ‘paragliders’, and another NASA engineer had ideas for a fabric-based steerable parachute for returning space vehicles to earth. He is David Barish, the subject of a 2001 article in CrossCountry magazine. He is rightfully regarded as the father of the paraglider, and created his own version of a spacecraft return device long before 3 French sky-divers flew their square sky-diving parachutes from a French hillside in June1978. Barish joined the United States Air Force in 1944, trained as a Mustang pilot and became operational as the war ended. Posted to Cal.Tec. he gained a masters degree in aerodynamics and worked for Air Force R&D at Langley. He left the Air Force in 1953, remaining a consultant for USAF and NASA. Revolutionary gliding parachute designs resulted, and his contribution to the 1960s space race was the Sailwing, flown in the Catskill Hills of New York in 1965

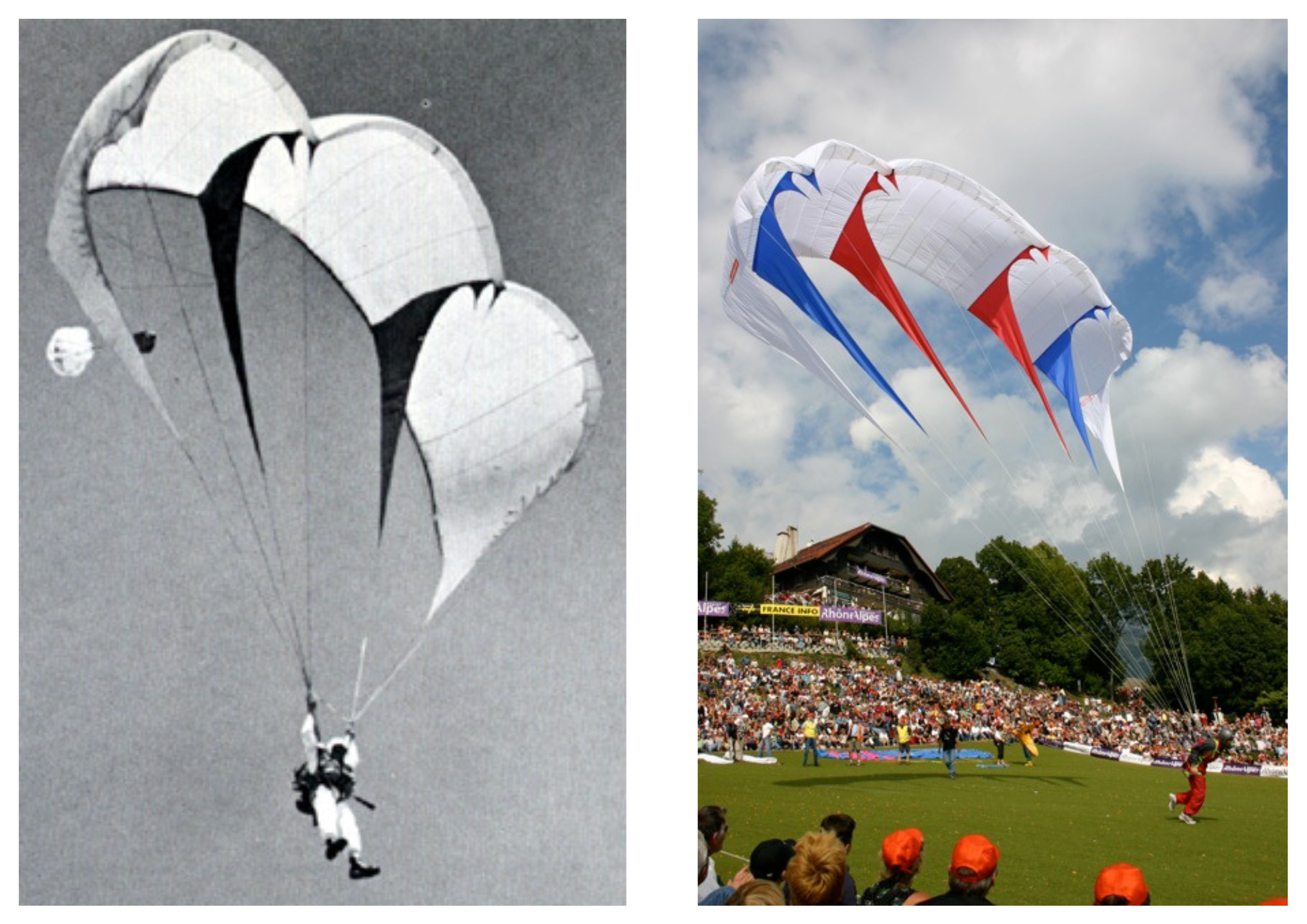

A replica was made forty years later at the most recent turn of a century. I saw it fly at the 2005 Coupe Icare, and a magnificent sight it was.

Left: Original 1965 Sailwing. Right: 2005 Sailwing Replica. Picture - Ed Ewing

Airborne development and testing of the radically different ideas ran in parallel for a couple of years - (1963-1965 approx), managed by the same people. These were Parasev and M2-F1. As tow-launch devices could they have been more different? Not really, and the lifting body principle seemed to make more sense as the staff became more familiar with the high airspeeds and rates of descent required for achieving a horizontal landing. I believe the last Parasev flight occurred in 1967.

However, the 2019 Rogallo Foundation post from Billy Vaughn explains another reason for the abandonment of parachutal devices in favour of lifting body aircraft. President Kennedy’s 1961 Moon Challenge specified ‘before the end of this decade’. 1960s government money was now focussed on Apollo development and all the other paraphernalia required to achieve this objective. Aircraft manufacturers were also attracted by the government support offered for future space shuttle development. The splashdown works for now - no more money for parachutal devices.

By then a variety of metal (heavyweight) lifting bodies were being tested and compared, all dropped from the B52 and capable of rocket powered assistance, either for ultimate speed research or final approach assistance.

The first 3 metal flying bodies

The basic shape of these strange creatures gave rise to debate and experiment. The lightweight M2-F1 was clearly flat on top and rounded underneath, but wouldn’t the opposite be better? The X-24B sort of settled this problem, and space shuttle design began elsewhere in 1968, but we did not see the finished product until 1981 The last Apollo moon landing mission ended on December 19th 1972 with the standard parachute splashdown. A nine year gap for TV enthusiasts.

What happened next?

For the TV public not a lot. The Moon challenge had been achieved, and everyone had got away with it (just). Where’s the story in that? In fact space derring-do now had a nine year publicity break. Rogers Dry Lake and the B52 were still busy, and plenty was still going on at Dryden research, but the public were bored with space stuff.

The first three metal lifting bodies became 5 if we include the HL10 which ‘handles better than some new fighter protos,’ some said, and the modified X-24A which became the X-24B. The X-24A (The Flying Potato) had been rebuilt with a flat slender delta wing underneath. It looks the business to me, and if you look closely you can spot some of the original potato on top. Work on space shuttle design resulted - technically a wingless lifting body spacecraft.

X-24B turning finals for the left desert strip

Space Shuttle

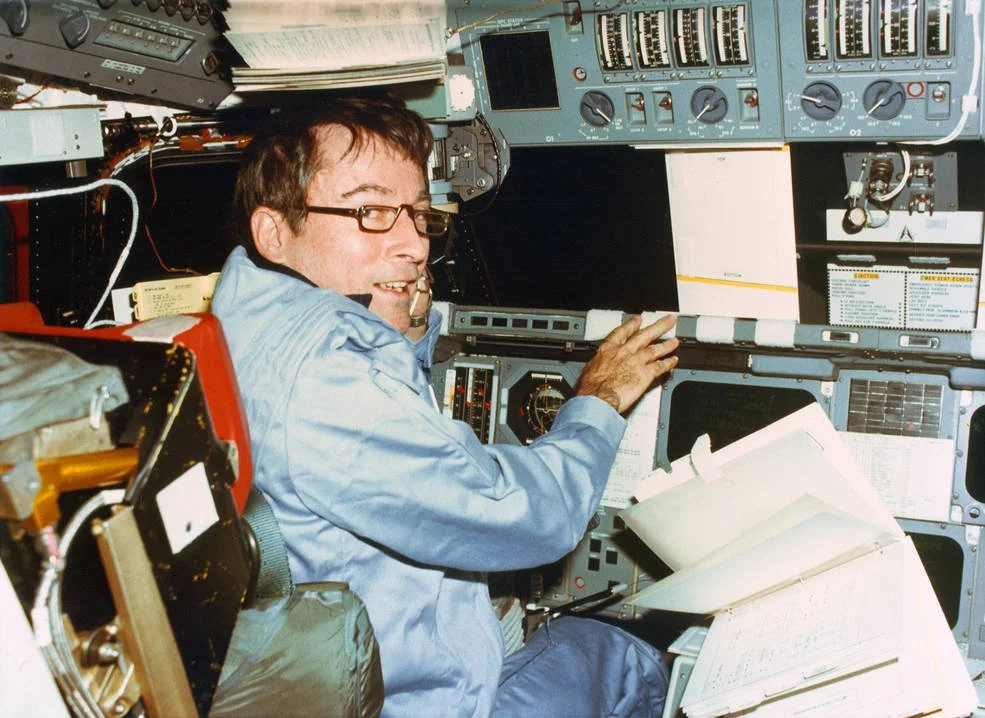

In 1981, 9 years after the Apollo 17 mission had splashed down we saw something new - a vertical space shuttle on the launch pad, ready to go. Wow! - the size of it: and the first rocket-powered flight into orbit would have a live crew of two. The whole thing worked, they orbited for a couple of days and returned to the lakebed for a nice hand-held landing. “The captain did a great job” said co-pilot Robert Crippen, after his first space flight. Here’s a picture of John Young wading through a list of system checks required during their 37 orbits.

John Young with paperwork during STS1

What about the floppies in space - today’s rescue paraglider - where is it?

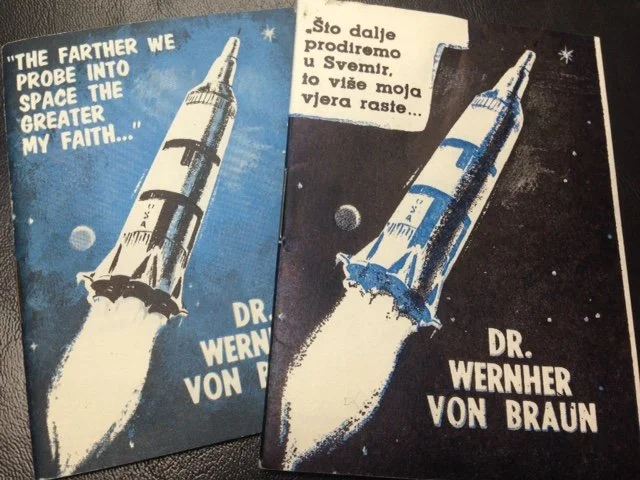

Believe it or not we haven’t got to one yet despite the 1965 Sailwing of NASA’s David Barish, recreated in 2005. But the problem of space station emergencies remains. A space station must remain in space; it cannot bring its occupants back to Earth. The unsinkable Titanic had lifeboats even if their use was not seriously considered, some have said. But the emergency repatriation of crew from space had been considered for many years, in fact Wernher von Braun raised the question in 1966. This was the year von Braun sold half a million copies of his booklet.

Von Braun discussing belief in 1966 on Assemblies of God radio, Texas

Originally a Lutheran-turned-atheist, von Braun now had taken the intelligent ‘don’t know - perhaps’ agnostic non-committed position. I understand. Recent astronomic advances in distance and time raise more questions than there are answers. Who can say? We must keep an open mind: and Von Braun seems to have been quite a diplomat. A clever man.

The X-38 was intended as a space lifeboat. The project was based on lifting body research with the title CRV: Crew Rescue Vehicle. ‘Return Vehicle’ sounded less scary, or finally ACRV Assured Crew Return Vehicle. I’d pick that one, but I did like SCRAM - Station Crew Return Alternative Module based on a big HL10 design, the HL20 - but its 8g touchdowns wouldn’t do your bad back much good.

The X-38 got as far as scale model testing, up to 80% of full size. After reentry deceleration, drogue parachutes would stabilise a vertical flightpath, followed by the unravelling of a magnificent and seriously big paraglider. Take a look at this one:

Looks like a giant paraglider to me

Parafoil is the army rigger’s name for a flying parachute - in this case a big one. A gentle landing resulted, with the strings all controlled remotely by a man in a shed elsewhere.

X-38 landing by paraglider

Around the turn of the century the US government decided that all this research was getting too expensive, and the X-38 programme was cancelled in 2002.

X-38 team photo

Artist’s impression of a SCRAM H20 at a space station

So, neither hang-glider nor paraglider actually went on a proper out and return spaceflight - just relatively low speed test flights. But the impetus given to the Vol Libre versions is responsible for an enormous wealth of understanding and, believe it of not, the development of much flying skill and quality decision-making under critical situations. I speak only for myself as a very ordinary 20 year paraglider pilot, so how does this compare with Concordeing?

Strangely similar in terms of individual commitment - at completely opposite ends of the speed and energy spectrum. Both activities require the following from its crew:

A continuous awareness of the importance of not getting caught out.

An understanding of what nature and Newton are telling you 24/7.

Not assuming you are safe because the marketing says so.

Understanding that you only get it seriously wrong once while engaged in flight.