Hangies (and floppies) in space?

I paraglided for 20 years, 1998 to 2018, but had no idea that the related, kite-based hang-glider was invented by a NASA staff member in 1948 as a possible means of getting brave astronauts down from a 17,000 mph orbital glide.

Marco Polo

The Chinese have been avid kite-makers for at least 3,000 years. Venetian teenager Marco Polo’s 1271- 1295 business trip to this unknown part of the universe brought many new ideas back to Europe. There’s something very modern about this super-rich entrepreneurial family. Father and uncle were both major players in the Venetian gold and jewellery business, with all the confidence required for such an audacious project. The silk route showed Marco how to get there.

Fiery Drake (Chinese fire-breathing dragon) woodcut

Here’s a German woodcut of a 1634 ‘Fiery Dragon’ kite in action. It’s simple by historic Chinese kite standards, but suggests that the gloom, fear and superstition of the European Dark Ages was finally giving way to a return of the creativity and imagination of Archimedes and Euclid et al.

The 12 year old Mayflower ship finally left Plymouth for America in 1620; a bit cramped inside because it also carried the Dutch pilgrims from the Speedwell (launched in 1573 as Swiftsure). The Speedwell sprung too many leaks as it addressed the Atlantic swell - too many shipworm holes. The shipworm is actually a little-understood wood-drilling shellfish: but to continue . . .

Was there a fiery dragon kite-flier among these hopeful Mayflower passengers? It’s possible . . . From personal experience I can tell the reader that there were some strange superstitious people aboard. They were going to be Americans after all, but doubtless there were also some with a pragmatic view of how the world could work, even in 1620.

Invention of the hang-glider

Francis Rogallo was a NASA engineer, not a pilot. He is unquestionably the father of the recreational, simple-handling hang-glider as we know it today, but that was not the original idea.

Author as a hangglider backseater

The idea of space travel long predates 1945, and the progressive end of WW2 hostilities permitted both East and West to discover what the others had been up to. Von Braun’s V2 seems to have become the most recognisable image for space flight fiction, though it was the Soviet Union’s Sputnik 1 which got there first. However, the safe return of a human to earth is far from straightforward, partly because of our atmosphere. To orbit the earth while mostly free of atmospheric drag, a minimum altitude of approximately 400 kms and a relative earth speed of 17,000 miles per hour is required, hence the fiery rocket ride to get there. All early manned spacecraft made their final 25,000 feet of vertical descent under one or more round parachutes, so where did the 17,000 mph go?

A lot of heat is the answer. Retro rockets to start with, followed by the capsule’s blunt end heat-shield during a carefully angled glide. The final parachute splashdown worked, but wouldn’t it be better to have something steerable for the last part, which could arrive predictably and horizontally on land, like a glider? Something like this, perhaps . . .?

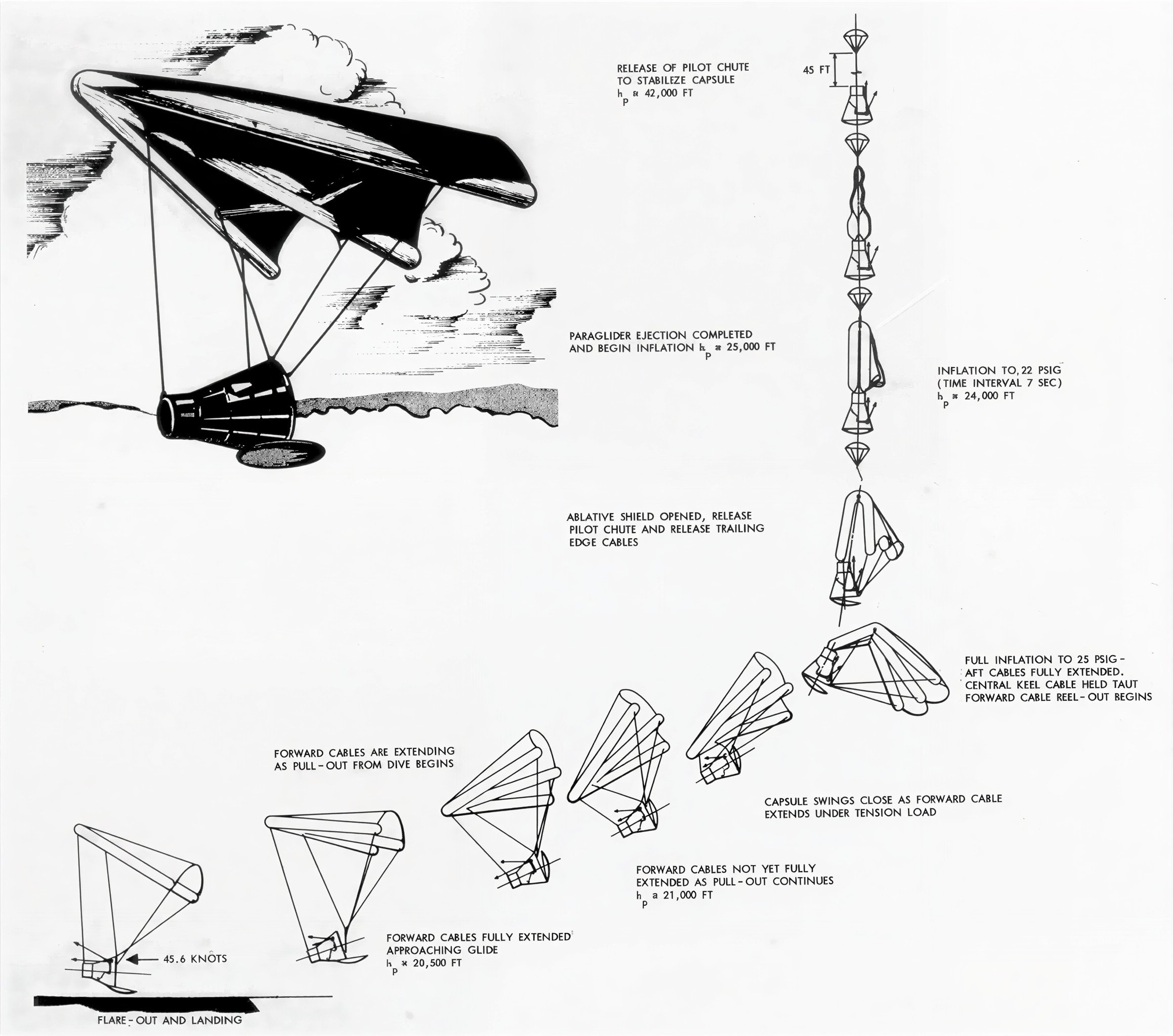

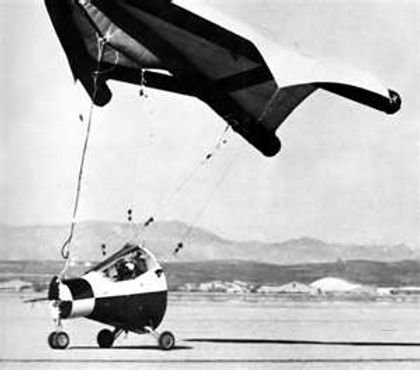

Rogallo deployment sequence

Rogallo gave this some thought, and had built his first garden shed kite in 1948. Its frame was simple: three light rods joined at the nose, and one cross-brace across the middle. Mrs Rogallo (Gertrude) cut out and sewed the fabric sail on the kitchen table. This cloth had started life as the kitchen curtains anyway, but the kite flew well, better than expected. He patented the design in 1954. Technical work including wind tunnel analysis continued, and Rogallo’s committee of three published a NASA feasibility study in 1960. Hang-glider pilots should note the Mach numbers and temperatures considered.

The cold war race for space

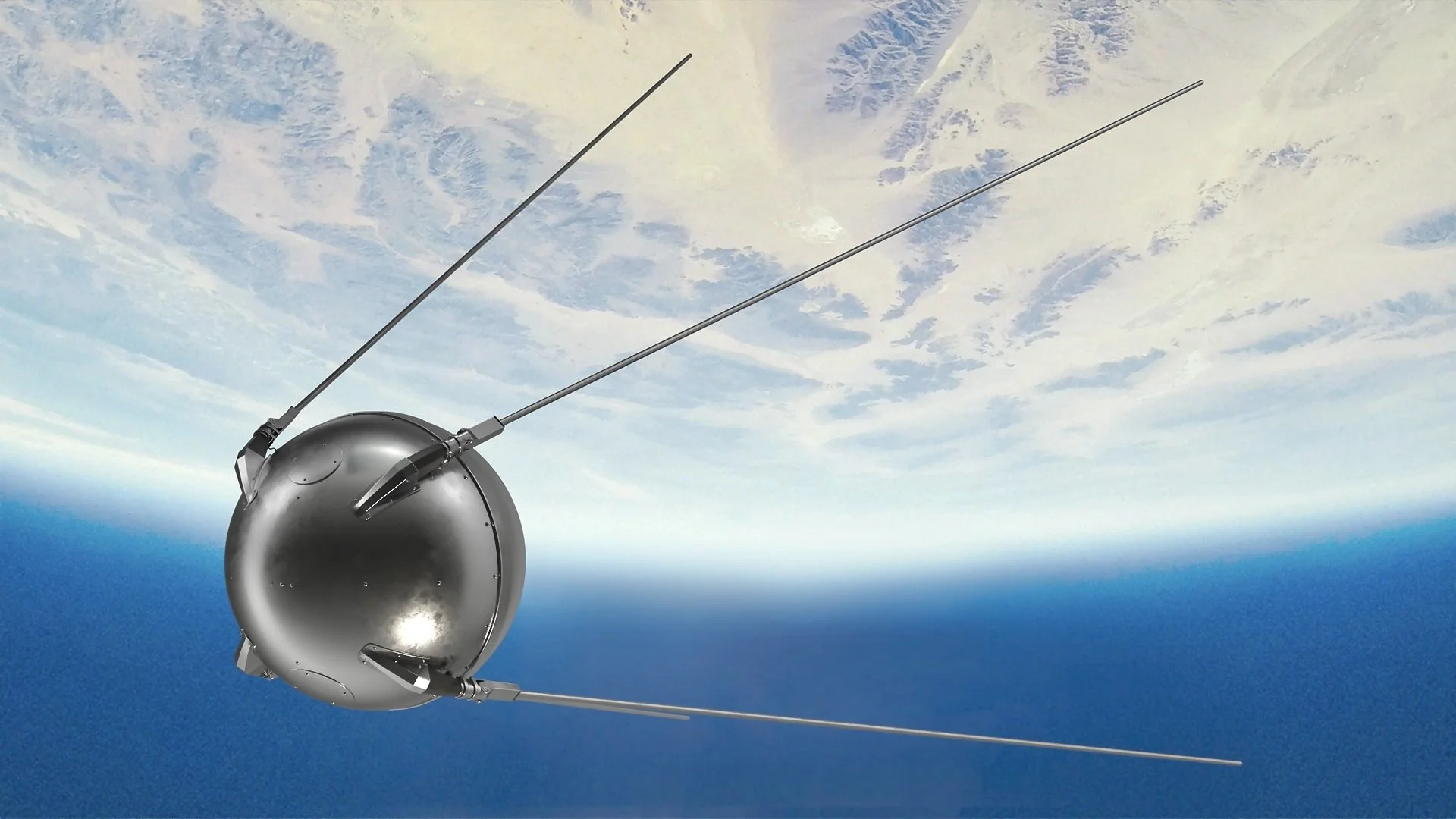

Sputnik1 - by Turbosquid

A Soviet surprise had already started the Race for Space on October 4th 1957 with the successful launch of Sputnik 1 into Earth orbit. The two foot diameter sphere only beeped, but the world could hear it. Aged 15 I remember listening to it on the family crystal set in a cold and dark house in an Oxfordshire village. The beeper’s batteries ran out after 3 weeks, but the little Sputnik itself achieved fourteen hundred 90 minute orbits, reentering on Jan 4th 1958.

Gagarin signing autographs

The first human in space - space parachuting begins

Brave MiG15 pilot Yuri Gagarin kicked off with a single orbit in April 1961. He landed by personal parachute, on a farm somewhere in Kazakhstan having left the trusty Vostok Mk1 at 25,000 feet on the way down - smart guy. Actually, the entire flight including ejection sequence neither required nor permitted pilot input - and he was smart enough not to press any mystery buttons. He landed a mere 300kms from his reception committee but in the right country, his first task was to find the farmer and phone Baikonur mission control to arrange a pickup.

Vostok 1 with Yuri mock-up

Telephoning head office was not easy in 1961, or even 1976 when the world aerobatic scene spent a couple of weeks in Kiev, but all ended well. Gagarin’s flight was a fantastic achievement in anyone’s book. The Vostok 1 was a steel sphere with a toughened glass window - aeronautically a large cannonball, not much of a glider. How hot did Yuri get before the cool relief of his parachute ride?

On May 5th 1961 Alan Shepard became the first American in space with a 15 minute, 300 mile sub-orbital flight, this time remaining in the capsule for the parachute descent into the sea.

Three weeks later President Kennedy really ramped up the pressure on his own brave fliers and researchers with the challenge to “Land a man on the moon and return him safely to the Earth by the end of the decade.”

Shepard winch up

This was achieved in 1969 with Apollo 11’s splashdown on July 24th of that year. What a decade of progress by trial and error, from both sides of the iron curtain: but where was the steerable NASA device that could land on a runway, and avoid this expensive and unpredictable boating? Delicate metal structures full of electronic gadgets do not take kindly to a dunk in the sea, and naval grappling traditions must be practical, so each splashdown was a spacecraft’s last flight.

Kennedy statement: Lyndon Johnson looks on

Apollo #17, the last splashdown (for the time being).

The Parasev, the Sailwing, or Lifting Bodies?

This essay considers the very experimental and superficially homespun tinkering that led up to the splendid space shuttle. Bizarre but true would cover the progress made in the early 1960s at the Muroc (or Rogers) Dry Lake.

We, the general public, only get to see the result of a newsworthy project. Parallel experimental work may have been underway for decades, and painstaking research might never attract public attention. Much will have been learned, many projects filed for posterity, and sometimes the results find favour with a completely different enthusiast group. This is what eventually happened to Francis Rogallo’s 1948 rod and kitchen curtain kite.

After patenting his design and carrying out full size wind tunnel testing, his findings attracted the interest of a number of NASA staff. His 1960 technical paper had been published a year before Gagarin’s flight, and two schools of NASA thought had emerged as to how best to manage the energy transfer of capsule reentry. The first priority is heat dissipation as the ever-denser air molecules are encountered, and the second - more of a luxury - a glide approach and landing on a predetermined runway.

X-1

The flat expanse of the Rogers Dry Lake in California had been used as a convenient landing ground since the 1930s, and its clear skies and relative seclusion made it suitable for air-dropped rocket-powered aircraft which eventually descend and land as fast gliders. Celebrated examples are Chuck Yeager’s Bell X-1 (flew 1945-) and the X-15 (1959-), and though these two machines happen to be devoted to high speed and altitude handling research per se, Cold War tensions rapidly identified the priority of outperforming a possible enemy in the air. Edwards Air Force Base, its associated Air Force Test Pilots School and their Navy equivalent were the places to go to identify suitable astronauts. This military tradition represents the second space return policy: spacecraft that could also glide well enough to make a horizontal landing on a dry and flat surface.

X-15

NASA at Edwards AFB, 1959-1971:

Paul Bickle was NASA aerodynamics research chief during these years when the return from space would be of prime interest. The Mercury Seven, America’s first astronauts, were announced in 1959. All were military test pilots, but Bickle, the man in charge of the science, is best known as a glider pilot. His 1963 height gain record of 42,330 ft still stands. He is well worth looking up on Wikipedia, and, strange as it may seem, there is a wise logic to his appointment as flight test director for lakebed landing research - virtually all the landings are made without power. This is something that jet pilots would usually prefer not to do.

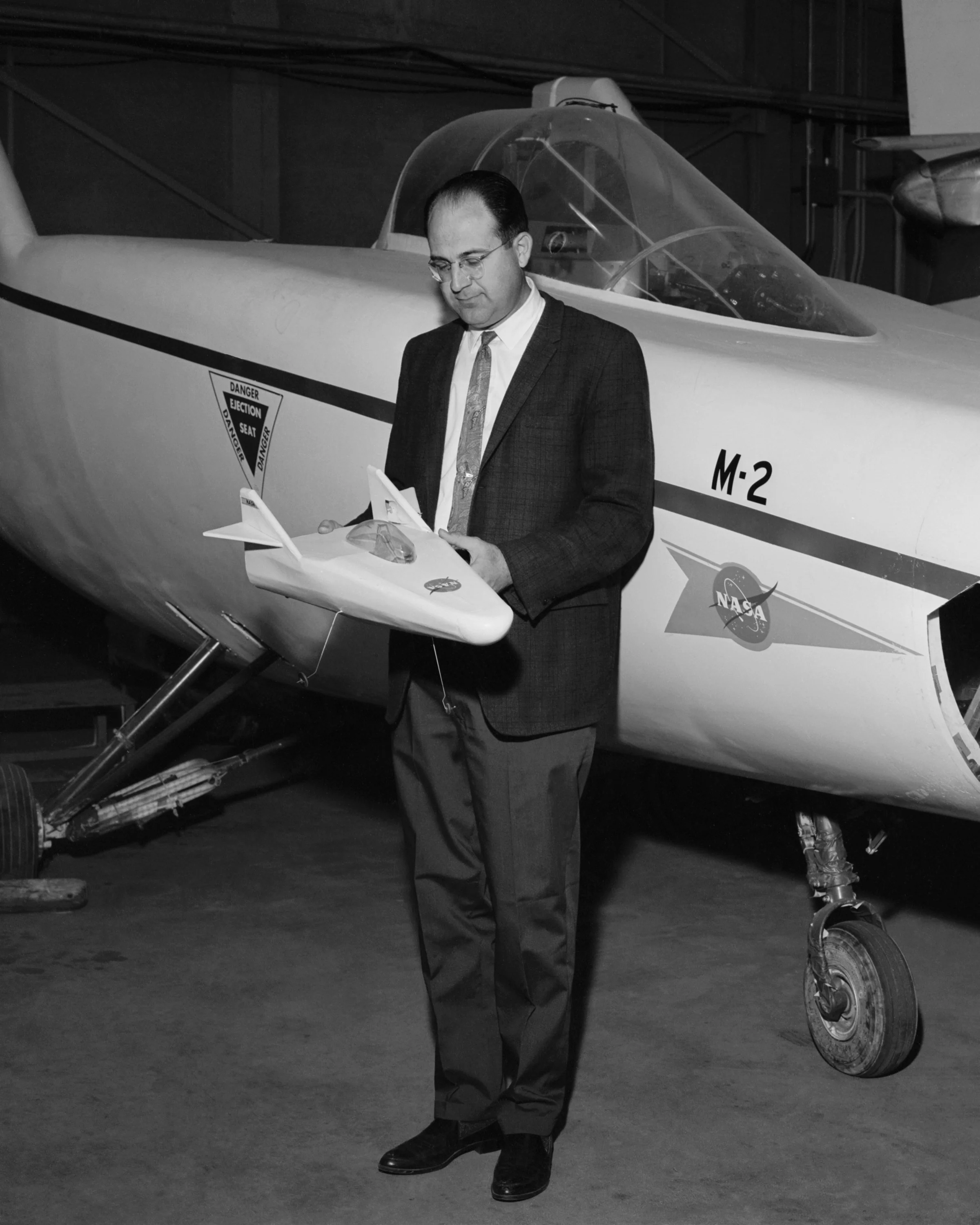

Paul Bickle

Paul Bickle was closely involved with the X-15 project and the future Boeing X-20 Dynasoar, but the project to explore a conventional landable alternative to the round parachute has few direct precedents. There is a particularly old-world charm and quaintness in this degree of inventive freedom. Success achieved by a determination to succeed is a special American quality, exemplified by the Wright Brothers. And although we should not forget the rocket technology acquired from Europe, the less spectacular but very important means of getting down is a classic story of homespun backyard creativity. There were two highly contrasting possibilities: parachutal devices deployed at low speed, and space-capable, self-contained flying objects with acceptable aerodynamic qualities for conventional landings. A sphere is the only shape that cannot provide lift - only drag - but any other shape can produce some lift. The remaining question is how fast do you have to glide to achieve level flight for landing your wingless spaceship glider?

ThIs was Bickle’s management task, and while most opinion favoured the fast gliding lifting body option of the future, the historic Rogallo Parasev (PARAchutal reSEarch Vehicle) was given its chance. The attempt lasted four years, within the 1960s, in fact a broad brush devision into decades may help the public reader form a clearer mental picture of this bewildering process of very varied and overlapping space exploration research.

1960s: Ever bigger rockets into Earth orbit, leading up to the moon landings. Returns to Earth exclusively by parachute splashdown. Parasev and lifting body research only.

1970s: Very quiet for the public, busy for those trying to find a return alternative.

Lifting body research prepares the way for the Space Shuttle.

1980s -1990s -2000s: Space Shuttle success, but 2 fatals, retired 2011.

Today: Back to parachute descent for 10 minute recreational space tourist flights.

The CFI

Paul Bickle gave Milton Thompson the task of managing the physical side of this novel research programme, despite Thompson’s preference for the wingless recovery option. He was to have been the only civilian test pilot to fly the Boeing X-20 Dynasaur, among a group of determined Air Force flyers, But he now becomes our project CFI (all types).

’Now for something completely different’ might describe the Parasev learning challenge, and my guess is that Milton’s age and varied career suggested a maturity of judgment that might be useful for a safe, if lengthy programme. Old enough to have flown the light and powerful Grumman Bearcat for the last few months of the War in the Pacific, Thomson continued flying in the Navy for six years, then did a little crop-dusting. So far this variety of piloting suggests useful experience to me. He then studied aerodynamics, achieving a BSc before joining NACA in 1956. There is little in common between military testing and scientific research, and he makes this difference clear in ‘Flying without Wings’:

NASA concerns itself with experimental research, aerodynamic innovation and subsequent device behaviour. On the other hand military test pilots investigate the behaviours and performance of military prototypes that have already been designed, constructed and tested elsewhere - as warlike aircraft, not spacecraft. These prototypes are assessed for their suitability as fighting aircraft. Handling niceties may not be a first priority.

Parasev testing started in 1962. Neil Armstrong and Gus Grissom became two of the helpers. Wind tunnel and theoretical aerodynamic analysis was readily available in the corridors of the NASA building, but the practical work of confronting the laws of nature directly was more find-out-for-yourself. Ground towing with a road vehicle progressed to light aircraft tugging, and work with the Parasev continued for 4 years, before parallel advances in wingless lifting bodies indicated the way to the future.

Dale Reed with wingless model

One project - two schools of thought

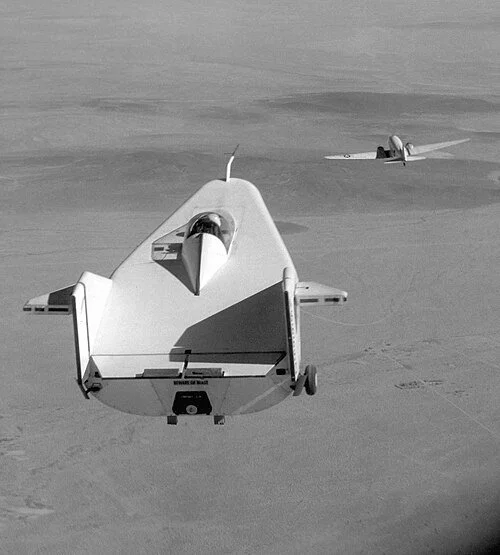

Parasev and M2-F1

A year into initial Parasev tests Milt Thompson had wondered what the pounding footfalls along the corridor outside his office meant one morning. It was aerodynamics expert Dale Reed towing a balsa wood and tissue model he had made at home. It was a true wingless aircraft and flew quite well. This model became the M2-F1, a lightweight lifting body glider initially towed behind a specially-engined Packard muscle car.

After considerable practice getting the feel for this strange aircraft it was then aero-towed to a respectable altitude. So radical was the thought of no-wings-at-all that the in-house enthusiasts had conducted their own project, using a local sailplane builder to make it. With the help of the man who had shaped the plywood panels for Howard Hughes’ Spruce Goose the M2-F1 made its first successful towed liftoff on Apr 5th, 1963, piloted by the CFI. Lift-off speed was 86 mph, but it flew. The initial success of the steel tube frame and elegantly shaped plywood outer surface of this insightful masterpiece should be considered another example of unconstrained American ingenuity.

M2-F1 and C47 tug

Parasev and M2-F1 programmes continued in parallel, involving the same staff5855, until the awkward Parasev was retired in1967. But the basic Rogallo found its destiny as a recreational portable foot-launched device for the people. Vol LIbre was born, and by 1970 the hang-glider idea had spread like wildfire among the thrill-seekers of southern California. In British Airways we used to retire at age 55. I’ve no problem with that, and it allows someone else to have a go. After 12 years of Concordeing I happened to take up modern paragliding in 1998 in Switzerland, and was impressed by the inclusive and matter-of-fact Swiss attitude to this way to fly. The formal school style felt familiar. One morning our teacher showed us ‘Playground in the Sky’, without explanation or introduction. Dating from 1970 the film deals with the chaos and fun of the Rogallo hang-gliding craze that had sprung up at Torrey Pines on the Californian cliffs near San Diego. Big hair, flared jeans, thrills and spills galore. Limited, if any, training in some cases. It captured the opposite approach to the Swiss teaching method - a warning to we sensible learners. Nothing else needs be said, but Playground is unmissable. Find it here.

What was wrong with the NASA Parasev?

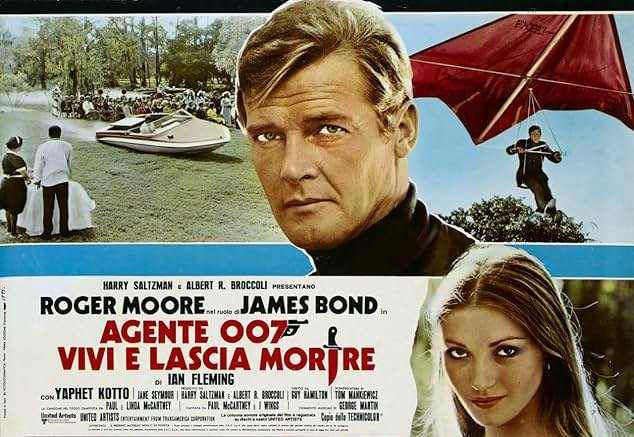

Nothing, but it was a research vehicle, intended to extend understanding, investigate possibilities, not come up with a finished product. Francis Rogallo’s simple kite device, invented in the 1940s, has proved itself to be a great controllable man-carrier - James Bond chose it for a covert Caribbean intrusion mission in Live and Let Die! But ideas change as time goes by.

After struggling with Parasev testing using experienced astronauts, CFI Milton Thompson got the impression that his select pilots appeared to have special difficulties when trying to manage this parachutal gliding device. He cites serious paragliding accidents elsewhere involving otherwise experienced pilots, and observed that novices seemed to progress better in this field than aircraft pilots. He’s right, and traditional joystick and rudder convention can be a hindrance.

The Rogallo kite, when flown as a simple man-carrying glider, is controlled by weight shift alone. Two axes of control, pitch and roll, are available: it works a treat. All ancillary weight is suspended from the wing aerodynamic centre, and pilot control is achieved via the trapeze-like cross member of a vertical A-frame fixed to a suitable point on the wing centreline tube. Unlike conventional piloting tradition, the pilot now has the complete wing in his or her hands - there are no control surfaces. Push your leading edge up (your weight back) to increase angle of attack becomes obvious the instant you grasp the bar. To turn right you lower your right wing: how to do that? Move your weight to the right via the A frame bar - push this to the left. Rocket science? Not really. It takes just one up and down, one left and right, and I’m sold: minimum handling complications, maximum capacity for tactical thinking.

Modern recreational Rogallo wing development

The picture above is from an article entitled ‘The Paraglider That NASA Could Have Used, but Didn’t, to Bring Astronauts Back to Earth’ written by Billy Vaughn in 2019, on behalf of the Rogallo Foundation and published by the Smithsonian Institute. The Foundation’s centre at Nag’s Head, N. Carolina, is just along the sand dunes from the site of the Wright Brothers’ giant step from gliding to powered flight. This historic coastal area also houses Langley airfield and its NASA presence, not far from the Norfolk Va. Navy Base and Patuxent River Naval aircraft test centre. It was written long after the abandonment of the Parasev project, but reflects the respect in which Francis Rogallo and his wife were regarded by colleagues and supporters.

The first Rogallo-winged Parasev had to be flown by someone sitting in the suspended sit-up seat on a kind of tricycle-undercarriage autogyro rig, equipped with a conventional pilot’s long joystick. How do you get the joystick to influence the wing in the same way? Pulleys and cables etc.. Trim is best accomplished by moving the load support point. Not so easy in flight. Was this possible? Following many tows across the flat lakebed Thompson’s first physically challenging glide after an aero-tow suggested perhaps not. But such was the euphoria at the success of this first Parasev high flight that, against his decision not do it again until the free glide control loads had been investigated, he made a second flight. Nothing had changed and everyone was happy, but he determined not repeat such punishment again.

Research went as far as a Gemini mock-up capsule suspended beneath the Rogallo wing, structurally braced by nitrogen-inflated fabric tubes in this later example. Towed up by a helicopter the pilot released and tried to position for a satisfactory landing on the lakebed. One pilot found that the Rogallo spun violently when released from the tow. He baled out and suffered a broken rib on landing. Another maintained control but met the runway at 1800 fpm. He was also taken to the hospital suffering from shock. The best lander was Jack Swigert, who went on to replace Ken Mattingley in Apollo 13.

In all, 6 Parasevs Mks 1 then 1A,1B etc made 341 flights between 1961 and 1965. For a list of talented, brave, lucky . . test pilots see Wikipedia ‘NASA Paresev’. None exceeded the 65 mph VNE under the Parasev.

Let’s leave it there, with acknowledgment of the remarkable patience and judgment of the CFI. The M2-F1 was looking more promising as experience of it was carefully gained. This lightweight homespun wingless radical glider set the scene for the variety of other metal wingless prototypes. He was always cautious - and right.

NASA and a kind of paraglider:

During these 1960s experiments all parachute-related devices were referred to as ‘paragliders’, and another NASA engineer had ideas for a fabric-based steerable parachute for returning space vehicles to earth. He is David Barish, the subject of a 2001 article in CrossCountry magazine. He is rightfully regarded as the father of the paraglider, and created his own version of a spacecraft return device long before 3 French sky-divers flew their square sky-diving parachutes from a French hillside in June1978. Barish joined the United States Air Force in 1944, trained as a Mustang pilot and became operational as the war ended. Posted to Cal.Tec. he gained a masters degree in aerodynamics and worked for Air Force R&D at Langley. He left the Air Force in 1953, remaining a consultant for USAF and NASA. Revolutionary gliding parachute designs resulted, and his contribution to the 1960s space race was the Sailwing, flown in the Catskill Hills of New York in 1965

A replica was made forty years later at the most recent turn of a century. I saw it fly at the 2005 Coupe Icare, and a magnificent sight it was.

Airborne development and testing of the radically different ideas ran in parallel for a couple of years - (1963-1965 approx), managed by the same people. These were Parasev and M2-F1. As tow-launch devices could they have been more different? Not really, and the lifting body principle seemed to make more sense as the staff became more familiar with the high airspeeds and rates of descent required for achieving a horizontal landing. I believe the last Parasev flight occurred in 1967.

However, the 2019 Rogallo Foundation post from Billy Vaughn explains another reason for the abandonment of parachutal devices in favour of lifting body aircraft. President Kennedy’s 1961 Moon Challenge specified ‘before the end of this decade’. 1960s government money was now focussed on Apollo development and all the other paraphernalia required to achieve this objective. Aircraft manufacturers were also attracted by the government support offered for future space shuttle development. The splashdown works for now - no more money for parachutal devices.

By then a variety of metal (heavyweight) lifting bodies were being tested and compared, all dropped from the B52 and capable of rocket powered assistance, either for ultimate speed research or final approach assistance.

The first 3 metal flying bodies

The basic shape of these strange creatures gave rise to debate and experiment. The lightweight M2-F1 was clearly flat on top and rounded underneath, but wouldn’t the opposite be better? The X-24B sort of settled this problem, and space shuttle design began elsewhere in 1968, but we did not see the finished product until 1981 The last Apollo moon landing mission ended on December 19th 1972 with the standard parachute splashdown. A nine year gap for TV enthusiasts.

What happened next?

For the TV public not a lot. The Moon challenge had been achieved, and everyone had got away with it (just). Where’s the story in that? In fact space derring-do now had a nine year publicity break. Rogers Dry Lake and the B52 were still busy, and plenty was still going on at Dryden research, but the public were bored with space stuff.

The first three metal lifting bodies became 5 if we include the HL10 which ‘handles better than some new fighter protos,’ some said, and the modified X-24A which became the X-24B. The X-24A (The Flying Potato) had been rebuilt with a flat slender delta wing underneath. It looks the business to me, and if you look closely you can spot some of the original potato on top. Work on space shuttle design resulted - technically a wingless lifting body spacecraft.

X-24B turning finals for the left desert strip

Space Shuttle

In 1981, 9 years after the Apollo 17 mission had splashed down we saw something new - a vertical space shuttle on the launch pad, ready to go. Wow! - the size of it: and the first rocket-powered flight into orbit would have a live crew of two. The whole thing worked, they orbited for a couple of days and returned to the lakebed for a nice hand-held landing. “The captain did a great job” said co-pilot Robert Crippen, after his first space flight. Here’s a picture of John Young wading through a list of system checks required during their 37 orbits.

What about the floppies in space - today’s rescue paraglider - where is it?

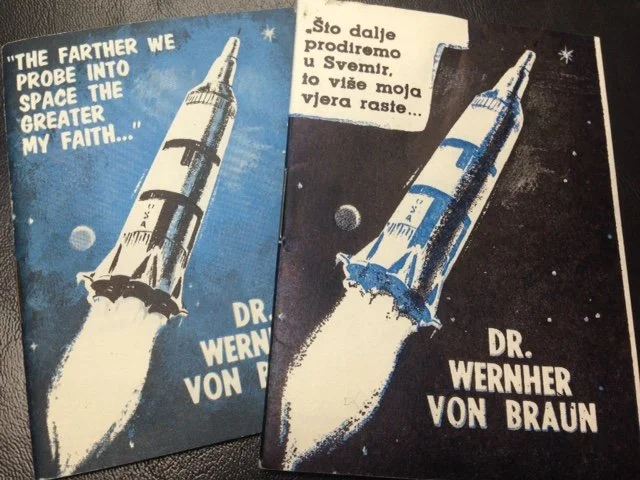

Believe it or not we haven’t got to one yet despite the 1965 Sailwing of NASA’s David Barish, recreated in 2005 (see pic 21). But the problem of space station emergencies remains. A space station must remain in space; it cannot bring its occupants back to Earth. The unsinkable Titanic had lifeboats even if their use was not seriously considered, some have said. But the emergency repatriation of crew from space had been considered for many years, in fact Wernher von Braun raised the question in 1966. This was the year von Braun sold half a million copies of his booklet.

Originally a Lutheran-turned-atheist, von Braun now had taken the intelligent ‘don’t know - perhaps’ agnostic non-committed position. I understand. Recent astronomic advances in distance and time raise more questions than there are answers. Who can say? We must keep an open mind: and Von Braun seems to have been quite a diplomat. A clever man.

Von Braun discussing belief in 1966 on Assemblies of God radio, Texas

The X-38 was intended as a space lifeboat. The project was based on lifting body research with the title CRV: Crew Rescue Vehicle. ‘Return Vehicle’ sounded less scary, or finally ACRV Assured Crew Return Vehicle. I’d pick that one, but I did like SCRAM - Station Crew Return Alternative Module based on a big HL10 design, the HL20 - but its 8g touchdowns wouldn’t do your bad back much good.

The X-38 got as far as scale model testing, up to 80% of full size. After reentry deceleration, drogue parachutes would stabilise a vertical flightpath, followed by the unravelling of a magnificent and seriously big paraglider. Take a look at this one:

Looks like a giant paraglider to me

Parafoil is the army rigger’s name for a flying parachute - in this case a big one. A gentle landing resulted, with the strings all controlled remotely by a man in a shed elsewhere.

X-38 landing by paraglider

Around the turn of the century the US government decided that all this research was getting too expensive, and the X-38 programme was cancelled in 2002.

X-38 team photo

Artist’s impression of a SCRAM H20 at a space station.

So, neither hang-glider nor paraglider actually went on a proper out and return spaceflight - just relatively low speed test flights. But the impetus given to the Vol Libre versions is responsible for an enormous wealth of understanding and, believe it of not, the development of much flying skill and quality decision-making under critical situations. I speak only for myself as a very ordinary 20 year paraglider pilot, so how does this compare with Concordeing?

Strangely similar in terms of individual commitment - at completely opposite ends of the speed and energy spectrum. Both activities require the following from its crew:

A continuous awareness of the importance of not getting caught out.

An understanding of what nature and Newton are telling you 24/7.

Not assuming you are safe because the marketing says so.

Understanding that you only get it seriously wrong once while engaged in flight.