Beginners’ Luck? Serendipity? An African Paragliding Story

Even in 2020, when arduous crossings of continents or dangerous mountain exploits at incredible altitudes are the regular stuff of paraglider adventure reporting, the ordinary amateur pilot still has the opportunity to achieve something unusual. The first rule: Be in the right place at the right time, and the second: You must not know that it’s impossible.

I started paragliding in 1998, at age 56. Inside information and an analysis of supreme skill in others tells me that ages of 7, 10, maybe 12 are better times to acquire the instinctive feeling for the special way a paraglider behaves, so that in later life a majority of conscious concentration can be focussed on important tactical matters. Learning the handling basics as an infant is the way the birds do it - and they make it look easy!

The outset

We were staying with Jan Minnaar at his Wilderness home, Cloudbase Paragliding on the south coast of South Africa. On this day there was a German group sharing the accommodation, as usual a collection of German friends ranging from beginners to long-term school members who preferred to stay close to the leader’s apron strings: the good schools cater for everyone. Their leader could have been called Manfred, I don’t remember, but he was keen to impress himself as well as his students.

“Where can we go to do some real cross country? This coastal stuff is all very well, but my party would like something more challenging, and your website mentions 40 sites.”

Every purveyor of paragliding knows this marketing problem, and the inexperienced client often has the feeling that his lack of daily success suggests that one of the secret 40 must be where he might achieve a BIG flight. But it’s the individual’s skill and experience that can produce a good flight – anywhere that’s flyable.

The Outeniquas

There’s a range of significant mountains that runs west to east for a considerable distance, paralleling the south coast of South Africa. These Outeniquas make a very clear dividing line between the green coastal strip, encouraging the Garden Route name, and the drier and hotter inland Karoo (meaning desert). Like other mountain chains they have a main ridge with foothills either side. Jan has been South African champion a time or two, and set the odd XC record along the road between the main mountains and the foothills on the hot side. These mountains look wonderful to an alpine flyer, but if you look carefully you can see the problems: almost no accessible takeoff places, and unless you follow the road there’s great potential for retrieve problems – much worse than Italy.

This was March 5th, 2006, and Jan took our party north; up and over the Outeniqua Pass then along the R62 Uniondale road to the Du Toit Gebruider’s farm. Not the place with the farmhouse and the brothers, but somewhere on their land, with a few ostriches, sheep and cows as the only living creatures; in fact we did not see another human soul or habitation all day.

Landing options

Before taking off the wise pilot should have some basic ideas about landing, especially in such a large and variable continent as Africa. It is not even like Switzerland. It is worth mentioning a rare but possible landing caution in this countryside. Do not choose a field that has a solitary black ostrich in it, or cows that has one special version among them. A thin, well-fit-looking dark brown one with a sticking-up mane, bayonet horns, a surprisingly long white tail and a beard should be avoided. It’s a black wildebeest – the cows’ friend but your enemy, and extremely aggressive. You cannot possibly outrun either of these creatures, and they will trash more than your glider.

Having transferred ourselves and what was needed for flight to the least valuable vehicle we set off on the tortuous drive up the electricity company’s road to where the aerial stood on this foothill. This is often the case in this country. Communications aerials have to be on hills, and the company own the only access road. Maintenance visits are seldom, and the rocky dirt roads suffer accordingly in the alternating heat and torrential rain.

Paragliding visits are rare, and each attempt is a gamble – you can be sure that the road (mountain track) will not have improved since the last attempt. A bit down the Karoo side there’s a place where the stones were moderately scattered. This is the takeoff.

More African terrain advice

Before we take off it’s worth mentioning some worthwhile homework. Find out what the dangerous snakes look like in your area. They do not want to bite you and will hide if possible, but you may fail to watch where you put your feet, or be plain unlucky. They are your friends really, and much less dangerous that some two-legged creatures. In the area of this story the snakes are the Puffie (Puff Adder) and the Cape Cobra. You cannot confuse them, but if you were to get bitten you need to know that all life-saving snake-bite serums are different. The wrong one is useless or worse. As your training advisor I advise a visit to a snake place and get to know them. It’s fun, good CRM, and probably less scary than you fear, and will provide some African snake-cred.

The takeoff site

We had arrived, and stood on the dry stony takeoff, facing north and the sun, with the pale grey silhouettes of the Swartbergs vaguely visible in the far distance through the heat haze. This distant range represents the next step up to the real Africa at 5,700ft. There is little wind; just a gentle thermal breeze coming up, perfect for now, which is why Jan has agreed to bring the novice kilometer hounds (in-your-dreams) up here. The odd small dusty is starting to get going in the dry landscape in front. A dust devil is only a rotating thermal you can see (because of the dust) but it has a worrying reputation because it could be described as a mini fair weather tornado.

The flight

Jan’s briefing indicates we should fly up and down this hillside and look for thermals. The landing area is to the right, on the flattish land in front. Simple enough, and sensibly so considering the variety of possibilities. There was no talk of big XC (or any XC, for good reason).

Before continuing the story it’s worth pointing out that although this is Africa’s equivalent of September, and we are at its most southerly part, we are no further from the equator than is Afghanistan. I’ve almost been there – as far as the Khyber Pass, anyway - and the heat and look of this landscape was quite similar. Jan had deliberately chosen this stable day, with high pressure to the north east of us.

I took off first with my Sigma 6 paraglider, with a few kilos of water in my cockpit bag – perhaps for weight, but definitely to drink if necessary. I searched along to the right as suggested, and sort of stayed up, but was making little vertical progress. Some others took off and struggled along in much the same way. I had the feeling that 1 pm in early September on a sunny day in Kabul should be better than this: why not try to the left – where the hillside continued to climb. Of course it worked better, and I started to find some nice circling 200m climbs. I had the impression that each new thermal was reaching 200m higher than the previous one, as the ground heated up and I encountered cooler air. What could be better?

As I climbed above the foothills my on-board electronic equipment showed the wind to be a light and steady NW, drifting me slowly towards the main mountains and the Garden Route holiday mecca far in the distance. There was no plan, but why not keep taking the climbs: there are agreeable options – be the first one to land near the Uniondale road and our car. But this current situation has a simple consistency to it: the higher I climb, the more I drift in the direction of home, and I haven’t run out of climbs yet. How many more do I need?

My radio hears Khobi, many times SA lady champion, report that conditions in front of the takeoff hill are getting very bumpy, and that the guests should fly out and land. I prefer not to do this, anything for an easy life. I’m not a total beginner. I already have 900 pottering flights in the Alps; that must mean something. I do not join the radio bonding session, and am pleased there are no requests as to my whereabouts.

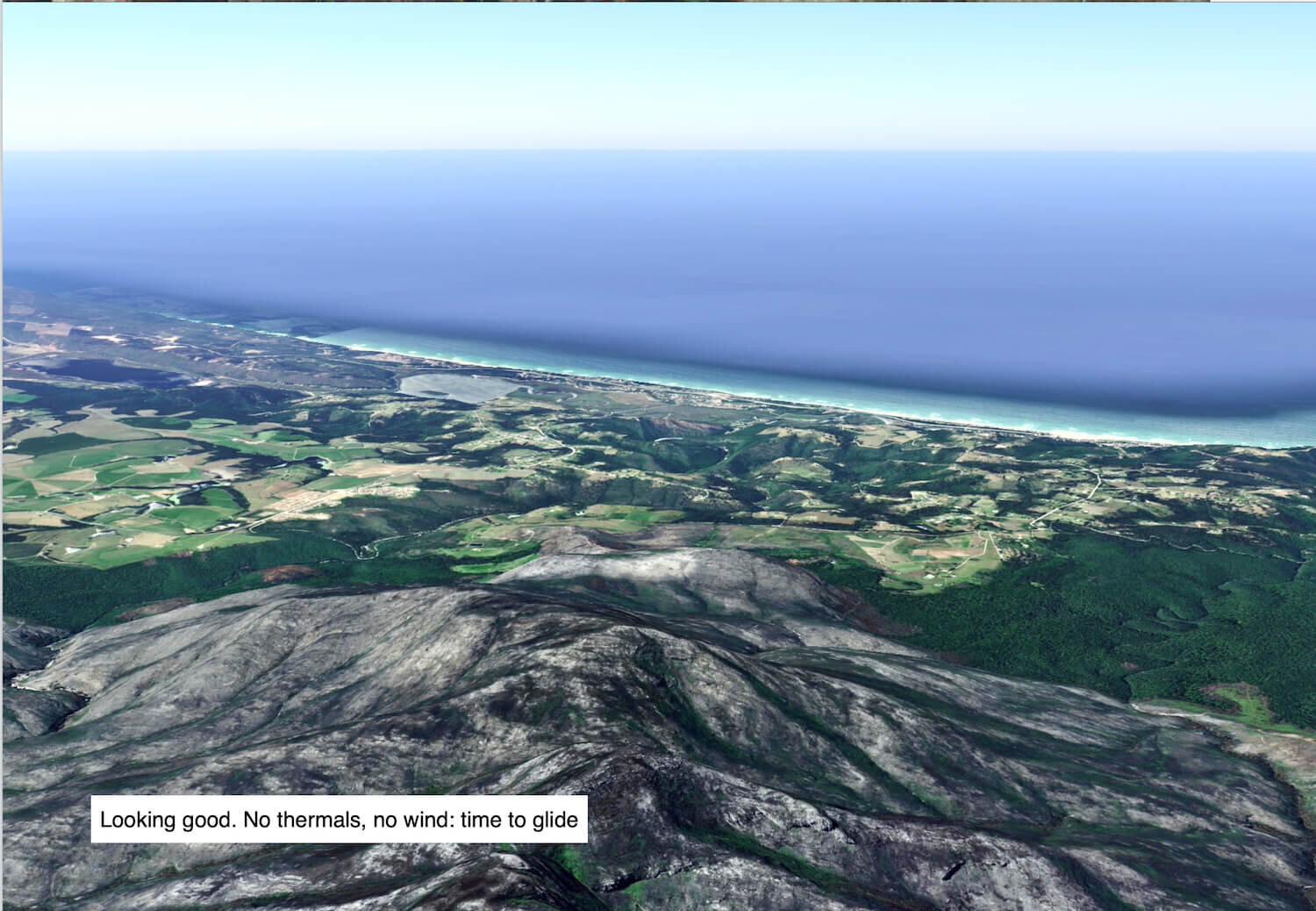

By the time I reach 9,000 feet above a distant sea level I’ve crossed the main Outeniqua ridge and am on the limit of my option to head back into wind and land by our hire car. Do I need to climb higher? Not really, and the climbs seem to be running out anyway as more of the scenery underneath becomes green. To circle over the jungly hills and drift southwards, hoping for even more safety margin, reduces the return option by the second, and a decision has to be made. Passing much of the mountain scenery and reaching the first of the green fields on the coast side has to be assured, but there’s no evidence to the contrary - unless some navigationally disastrous sink seizes me, or high level south wind suddenly sets in. But it looks good, and the sense of commitment, other options abandoned, frees the mind. I head south, hands up (best glide), ignore other distractions and allow the Sigma to glide downwind. This is proper free flying! Isn’t it nice.

Nice green-swarded hillsides – perfect for hiking?

The visitor to South Africa should be aware that the agreeable-looking mountains are not covered with knee-high shrubbery. That’s what it looks like from a distance, but the shrubbery is a lot higher, tightly packed, and the ground underneath goes up and down more than you would guess. There are few roads or tracks, and if you were to make a soft landing in the ancient and highly-convoluted trees of the lower slopes, what then? Leopards live in these inaccessible regions – and they have the strongest bite per size of any seriously-biting creature. A walkout, if possible, would take for ever. And this is their home – think about it.

The rest of the flight

Plain sailing; compared with a Grindelwald First to Interlaken beginner’s XC child’s play itself. The upper 15kph cyclonic flow above has to be affected by the Outeniqua ridge somewhere along my track as I descend, and, sure enough, it gets bumpy with sink as the Sigma slips below the mountain tops behind, but this can’t last for ever – and it doesn’t. Suddenly it’s glassy smooth, and groundspeed equals airspeed. There is no sea breeze at all, no evidence of thermals, wind on the sea or gliders on the coast. The air is completely calm – definitely no good for paragliding – except from my vantage point. The view is fantastic and, as it turns out, unique.

I approach the coast with tons of height (it’s surprising how well paragliders glide if you allow them), and head for the field near Jan’s house, but there is time to consider the situation. I have no house key, and all the others are sweltering in the Klein Karoo. It’s 3 o’clock and they won’t be back for hours.

A cruise along the coast shows one hangglider make a top to bottom at the Map of Africa - Johan’s student - and I head in that direction, turn round at Dolphin Point and land on the beach abeam the village where there is shade and a drink. I telephone our leader with my iphone.

“Don’t look for me, I’ve gone to Wilderness. Karen can bring our car back,”

“Where did you land?” asks Jan.

“On the beach, by the station”.

“Congratulations, you have the record.” He says. I’m amazed.

“What record?”

“No one has done it before. We’ve tried but the sea breeze always stops you.”

Next day we went game-parking, and Karen’s SD card with pictures from the K.Karoo takeoff spot with dusties in the flatlands got lost. Shame. But Manfred was fired up by the prospect of this easy XC, and insisted his group go back to Du Toit’s Farm for another attempt. One of his students did make it over the foothills to land by the road, but the leader tried too hard, perhaps, and stayed up too long against the increasing south easterly wind – normal conditions. Members of his group told me he landed going backwards in an unfriendly dry river bed some kilometers further towards Afghanistan than the takeoff site.

A couple of days later I met Craig, a local paragliding loner. Pleasant actually, a bit unconventional, but visitors are socially neutral - no flak. He’d heard about the flight. “Was that you?” he asked, when it became apparent. “Put it there” he said, shaking my hand eagerly.

“Why hasn’t anyone else done it?” I asked.

“They’re too scared” he said.

This is fun paragliding.

[Note 1. from 2019. Our great swiss paragliding maestro, Chrigel Maurer, 6th consecutive winner of the RedBull X-Alps race, now provides coaching presentations based on video footage and reallife in-the-race experience. Extensive preparation, planning, and meticulous attention are paramount, but he now includes completely spontaneous decisions to suit conditions. ‘Sometimes there isn’t time to analyse. If it works, go!’

Note 2. The Google Earth pictures, included to give an impression of a paraglider view, show the mountains as bare stone, after extensive bush fires. Most of the time they are a more inviting green colour.]