Concorde - for real

An Introduction

On June 18th, 2020, the President of France and PM of Britain celebrated the 60 years since President de Gaulle gave his speech from 10 Downing Street to encourage his countrymen to maintain heart and resist all attempts to extinguish the character of their country. Help is on its way, and will restore your freedom — eventually. He was right, and the Patrouille de France will join the Red Arrows in a symbolic demonstration of the sense of unity that joins these two long-associated countries, weather permitting, and despite many historic disagreements about almost everything; but relatively trivial and superficial by comparison.

This war did end, to change the world for ever, yet again. Creative minds tend to be devoted to their subjects in preference to politics, nationality and language; and German research and scholarship was eagerly offered new opportunities on both sides of the Atlantic and the Iron Curtain. Von Braun’s V2 rocket technology continues today in the USA. The expert who ended up in the Soviet Union preferred a collection of smaller rocket motors, similarly demonstrated today. The Austrian alpine water-powered wind tunnel resides in France — the Geneva water fountain demonstrates where the power comes from — and this device was very useful for Concorde research, but there is an important British aerodynamics connection with the land of Wagner, and, of course, its ‘Handy Hock!’ and ‘For you the war is over’ quotes.

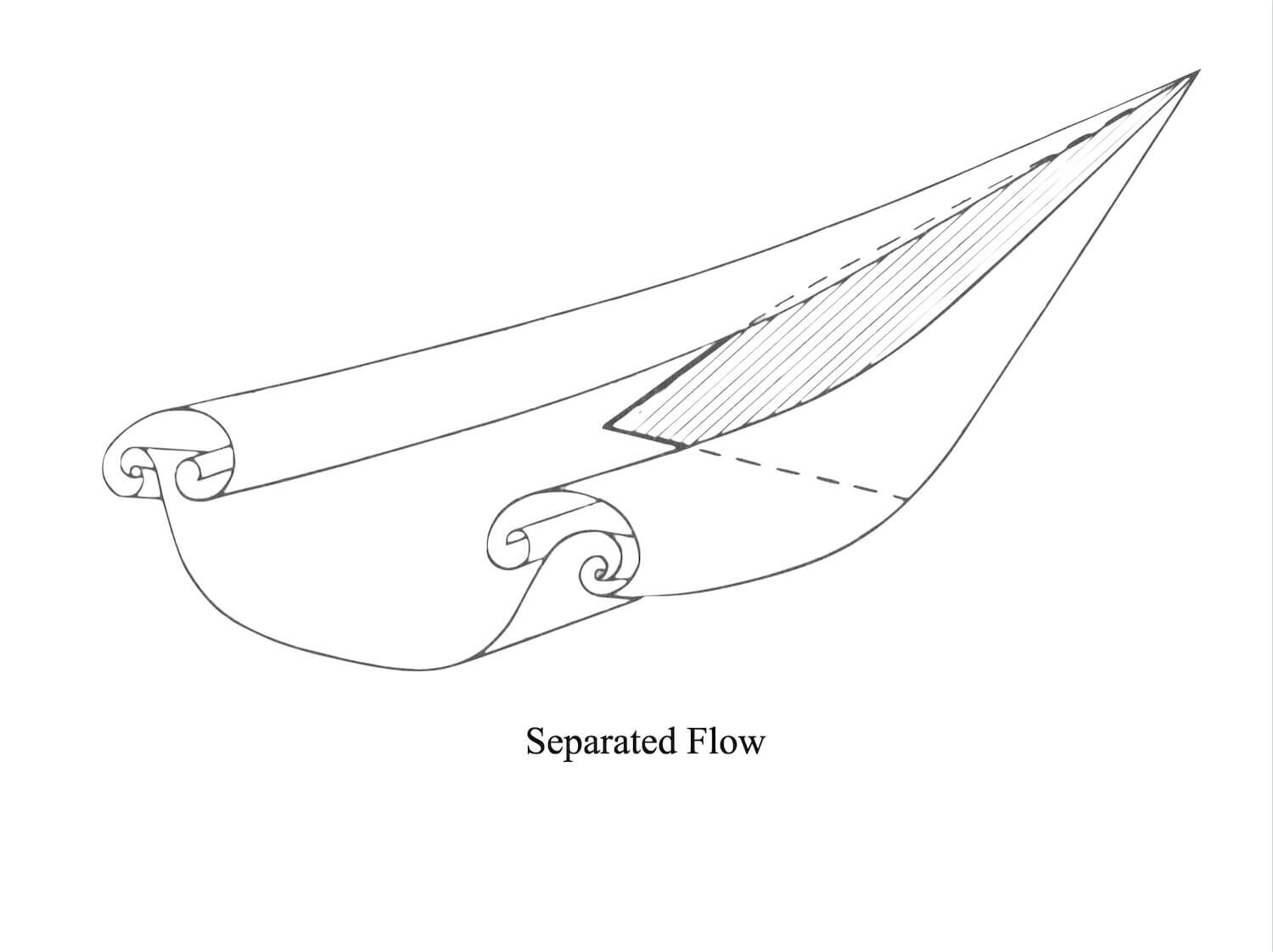

Dr Dietrich Kuchemann came to Farnborough from the German aerodynamics research place in Braunschweig. His job there was the improvement of fighter performance. This was where the Boeing design man had his Eureka moment in 1945. He was sufficiently impressed by the sophistication of their high speed understanding that today’s airliner layout was immediately brought to life by the B47 jet bomber prototype in 1946. A supersonic airliner is even more difficult, and it was Dr Kuchemann who eagerly proposed the slender delta, separated (stalled if you don’t like) flow principle as the answer to the necessary compromise between very fast and relatively very slow. The Concorde has 1000kts difference between cruise and landing speeds, 1,150 down to 150 kts — without a change of aerodynamic shape. Many said it can’t be done. Here is Dr Kuchemann’s drawing of the low speed airflow

Sir Archibald Russell, chief designer at Bristol, describes the concept and associated scepticism in his book ‘A span of wings’. This paragraph compares the idea with the double-swept M shaped wing

The second proposal, of breath-taking novelty, was based on a sharp leading edge on a narrow delta wing. With immediate separation at the (profile) nose the airflow then rolls up into a strong vortex over the wing: this flow was described as being so strong and stable that external lateral flows were of no consequence. Also, the stall (the danger point on conventional wings) is greatly deferred, with lift increasing faster than linearly, so giving the effect of landing flaps without flaps. We learned with much surprise that there was no penalty in aerodynamic efficiency.

Everyone knows that anything can be made to fly if it can be persuaded to go fast enough, so, having dealt with the slow end it’s time to start the story.

My first flight in a Concorde

A couple of months before my Concorde course started in 1984 I went on a look/see New York flight as extra crew with Jeremy Rendall. He must have then flown the Concorde for perhaps six years, but, like me, was not a bedroom desktop supersonic jet pilot. He actually flew the real thing on a regular basis.

I knew no more about the Concorde than anyone else from the outside world, and had never seen the simulator. I sat in the jump seat behind the captain to see what happened. The standard airline things were normal in style — checking around the panels from memory, reading the checks, starting up and so on were familiar, but most of the subject matter was different, and perhaps there was more of it. And there were a lot of strange engine topics. No mention of flaps, of course, but centre of gravity position was clearly important. Because the Concorde retains its basic shape for all regimes of flight, the aerodynamic considerations were of Tiger Moth level, including setting the takeoff trim (2/3 forwards for the Tiger, 2½ down for the Concorde, every heavy takeoff). Apart from this traditional trim feature there were none, not even unlocking the slats.

We duly took off and shook gently as we proceeded into the sky. But it all felt very purposeful and deliberate despite the shaking — no rocking around: a solid ride I thought, and very little moving of the controls once we were airborne. Eventually, after a countdown, we had a big noise abatement cutback, power adjustments, a lowering of the nose. But soon we left 250 kts and smoothly proceeded to 400kts on the clock and 4,000 feet per minute climb, then levelled out at 28,000ft over Bristol. Just like a Hawk (mini-fighter)? Actually yes. Jeremy turned round and said ‘Jump in, you can fly the accel.’ With that the copilot got out of his seat and ushered me into it.

Accel means the steady climb with accelerating airspeed, through Mach 1 (the fabled sound barrier) to Mach 2. Wow! Is he serious? I’ve never been supersonic before, even as a passenger. Of course, his confidence belied the Concorde’s agreeable nature when doing the very thing it was designed for.

We were flying in clear sunny weather, definitely visual flying conditions, although the distorted picture of the horizon ahead through the long sloping greenhouse visor did not encourage a seat-of-the-pants technique. The artificial horizon in front of me reminded one of the 747 I had left nine years ago, but was a larger, more up-scale version with extra accessories. Pitch attitude indication was detailed but clear, and Jeremy first told me about the yellow pitch bug and its thumbwheel on the controls, adjacent to your outboard thumb.

‘Set it to 7⁰,’ he said, ‘that will your first attitude when we start to climb.’

Our current pitch attitude was almost 5⁰, indicated airspeed just below 400, Mach number 0.95, Concorde subsonic cruise speed. ‘Press the autopilot button and fly yourself, the accel point is four minutes ahead.’ (This position is just past Cardiff, and 30 miles from a widening Bristol Channel coastline.) To begin with I did nothing, and nothing happened. Tiny exploratory up and down gestures were answered directly by the nose, which showed little preference. Solid but immediate and precise, I felt. Something distinctly neutral about it, then I tried the roll. This was a surprise. I was currently flying the 707 quite a lot. While excellent in its own way this machine’s gentlemanly rolling equipment could not have been more different from the Concorde’s full span powerful and electrically signalled roll controls. The smallest break out gesture created a lurch to the side which was immediately countered by unseen external forces. If I’m not especially careful with this there will be complaints from the back. Fortunately the next miles were straight, and I can reveal that I might have discovered a special feature of the difficult trans-sonic regime, but this and other trigger warning subjects can wait for a future chapter.

Accelerating climb

‘Accel point’ was announced, followed by ‘climb power’ at which I opened the throttles. When the gauges were steady came ‘inners’ then ‘outers’ from the flight engineer. This moderate reheat does create a gentle but clear push and the passengers are warned about this unusual shove, but many are regulars, and familiar with the experience. My indicated airspeed immediately reached 400, the veeder counter readout being by far the most eye-catching choice of indication, and raising the nose to 7⁰ on my yellow bug did indeed steady the speed reading. We rapidly reached the next point of interest for the flying tourist, the barrier.

Disappointingly there was no bang, no shaking, shuddering, fighting with the controls, but the static pressure instruments were the special novelty. The vertical speed indication descended to the bottom of its strip, then as smoothly rose to the top of it, and returned to its original value as if nothing had happened (I think this is the right way round). The altimeter also did its diving and climbing then we were fully supersonic, with nothing else to show for it except a steadily rising groundspeed and Mach number. Apart from my own inputs the Concorde proceeded completely smoothly as if made for this supersonic business. Well, of course it was, hence the strange shape, and throughout this passage through the transonic zone the physical handling of the machine was totally consistent and conventional. Whatever pitching moments, shock wave effects on the controls or trim changes are associated with this battle with the air I did not notice. We climbed onwards and upwards, I did very little except steady as she goes.

[A handling note from the old (safe) days. When flying through the sound barrier, either way, using the autopilot, attitude hold has to be the mode to use. But It can be a life-saver in conventional airliners as well, and the same advice goes for thunderstorm type turbulence with its monster columns of rising and descending air. Keep the ship on an even keel, leave the engines at cruise power and let the vessel ride the storm, whatever the instruments say, or whatever else happens. This may not be so easy with a modern flight management system and fly-by-wire help usurping your authority, but bear it in mind. The Concorde did not have this problem. Instant attitude hold was readily available.]

And so we continued. Jeremy told me to follow the VMO pointer (velocity max operating, i.e., full speed to employees) as it now made its steady way to 530 kts: ‘5⁰ pitch and keep the needle in the VMO cutout.’ At forty something thousand feet we reached the 530 number at the same time as Mach 1.7. ‘Reheats off, eleven minutes’ said the F/E and we continued climbing at 530kts. Apart from staying on our inertial track and making barely perceptible adjustments to keep the rising airspeed on schedule — the smallest pressures were quite adequate — there’s little else to report about this novice’s assessment of how to drive a Concorde, except that it was unlike anything else of my experience.

Did I have to do much trimming? I don’t think so, perhaps the occasional nudge, but can’t remember. We reached Mach 2 at about 50,000ft and Jeremy said ‘That’s it for two hours’, and put the autopilot in, and cruise rating was selected in the ceiling. The rpm dropped back a couple of percent, to a mere 100%. Lunchtime. I went back to the seat behind the captain.

The cruise (climb)

During the cruise/climb we got slowly higher. There were no turns (great circle track), we chatted, ate our lunch (small and nice), and Terry Wogan signed a Concorde postcard for me. (I’ve never told anyone about this before.) Though we reached 58,000ft today the look of the sea and clouds far below still gave a more agreeable impression of movement than when trundling along at .83 at 35,000ft. A jumbo 20,000ft below us looked like a jumbo 20,000ft away — you could see what it was, if small — but it was going backwards at Mach 1.1. This was a major indication of what this Concorde ride was all about (and the sense of trivial satisfaction to go with it, infuriating to others, though never admitted. Definitely another emotion to go into today’s popular racism box.)

Coming down

At exactly two hours after pressing the takeoff watch we passed 50⁰ west (always the same 2hrs), then it was time for careful checking of the deceleration distance to the descending Mach 1 point, and a careful eye on this critical inertial distance-to-go. It’s surprising how a hefty-looking distance can catch you out at 23 miles a minute, and after the level flight slowing to 350, gliding (supersonic) at 350, levelling at 41,000ft, warming up the engines for one minute while renegotiating the barrier — again in attitude hold — the captain said‘, Jump in and have another go.’ I did so, and followed the steers and descents until it was obvious that I should get out and let the licensed crew continue - certainly before we had to fly at only 250 kts, and eventually quite a lot less.

Final approach and landing

As a standard subsonic airline pilot I could take little from this experience. It all looked straightforward: calm dialling of speeds, headings, but nothing else except wheels and droop nose. Landing? All very nose up, seemed OK, nothing happened, nice touchdown, huge lowering of the nose, but that’s what you would expect. If they can do it so can I. That was my hope, anyway.

The return to London

This JFK arrival touched down at 9:20 am local time, airfield and terminal deserted. I hung around in the JFK operations room. ‘Hey Captain, haven’t I seen you before, VC10s, 747s, 707s way back; remember those freighters? Yes, all this was true, and the American approach to flying affairs, whether military or civil, has a practical and helpful attitude that I can only commend. It functions regardless of status, but this subject is best left to other more relevant blogs.

The crew to take the same aircraft back to London turned up, and had presumably been warned of my presence. Brian (Titch) Titchener was the captain and showed no sign of distress so this must have been the case, and the return flight went similarly smoothly. Once round the Ockham hold at 250kts then in to land, local time about 8:30 pm, still in mid-summer sunshine. I drove home.

First impressions

Three hours thirty chock to chock is not so different from Comet or early 707 all points east sectors, but the Concorde Atlantic flight felt completely different. The subsonic and supersonic environments, variety of heights and speeds and the lack of a constant parameter cruise avoided the sense of now that we’ve levelled off we have to wait. Any idea of ‘they put it on George and do nothing’ was even less appropriate than usual, even if the Concorde autopilot flew more perfectly than a pilot. But the remarkable thing was the lack of the physical sensation of having been on two transatlantic flights. In the fullness of time I came to some conclusions about this: low cabin altitude (5,000ft), rock steady ride at speed, no ozone inside and enough down time between flights to prevent the upholstery chronically drying out. I drove home without the sensation of having been anywhere in an airliner: remarkable. But I was under no illusion that the apparent simplicity with which the crew went about their job did not conceal a large number of new things to be learned and understood, and there was little empty time with nothing that did not deserve to be thought about. The normal checklist was thin, though each item relatively lengthy, but the emergency checklist thick, with incomprehensible subject matter in it. Had I made the right choice? Definitely.